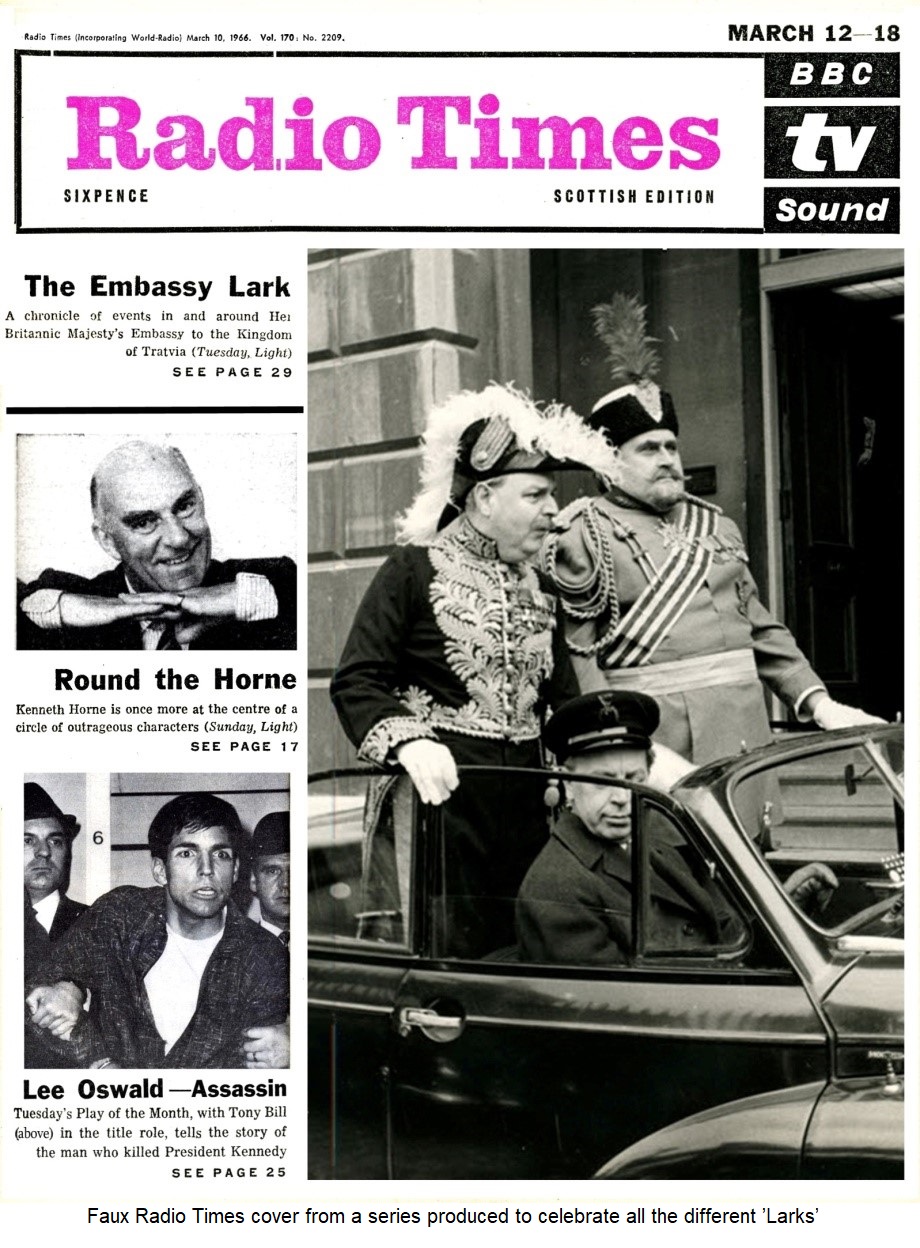

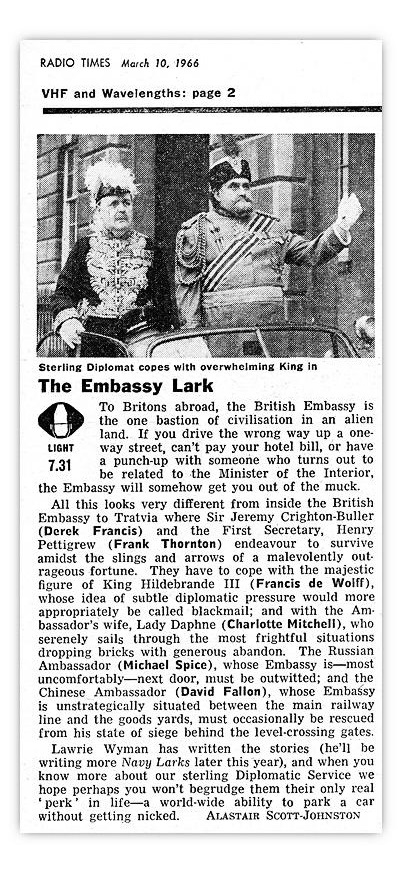

The Embassy Lark

‘The Embassy Lark’ became the third incarnation of the ‘Lark’ entertainments devised and produced by Alastair Scott Johnston and Lawrie Wyman. It ran for 3 years between 1966 and 1968 and enjoyed good audiences across the three seasons. Extra shows were added in years two and three, with thirteen episodes becoming fifteen. It could be argued that delaying the broadcasts by 90 minutes in Season Two meant that growing television audiences were having an impact on listening figures, especially as there was no Home Service repeat.

The production team recognised that the winning formula honed in ‘The Navy Lark’ highlighted the personalities of a small group of people of different backgrounds and ambitions stuck in a location with recognisable and believable traits. These realistic but imagined approaches to work and social life gave the listener a chance to be part of experience, and for many a chance to relive their National Service experience but without routines.

`The Embassy Lark’ was a chance for Lawrie eventually to write about civil servants and the hierarchy in government offices, as proposed in the rumoured ‘Whitehall Lark’ from late 1961 or early 1962. Given that the Pertwee family was credited with being omnipresent throughout the Admiralty and other government circles, it is logical to see how Lawrie would see that wearing a bowler hat and a pin stripe suit is not so very different from the Senior Service. It is suggested that the idea was declined but within the year `The Men from the Ministry’ arrived, which just might be coincidental.

Edward Taylor’s cast for MFTM was smaller than ‘The Navy Lark’, and like ‘The Island Draft’, storylines were strong on personality traits, incompetences, social dynamics, and light hearted satire of central government. Civil servants spoke with `received pronunciation’ accents that supposedly meant good public school education and therefore competence. However, lesser post holders’ voices demonstrated greater familiarity with the wider community due to secondary school experience.

`The Embassy Lark’ moved incompetence offshore to a country identified as Tratvia, presumably an Iron Bloc dependency in the East. By adopting an imaginary state, the writer(s) were able to be both different from and the same as `The Navy Lark’ and MFTM. Pomposity, aspiration, class, carousing and incompetence are common themes but we now learn these are no longer purely British traits, but also the observable practices of fellow diplomats from around the globe who have ended up in this unremarkable country without any political value or substantial standing even in its own federation.

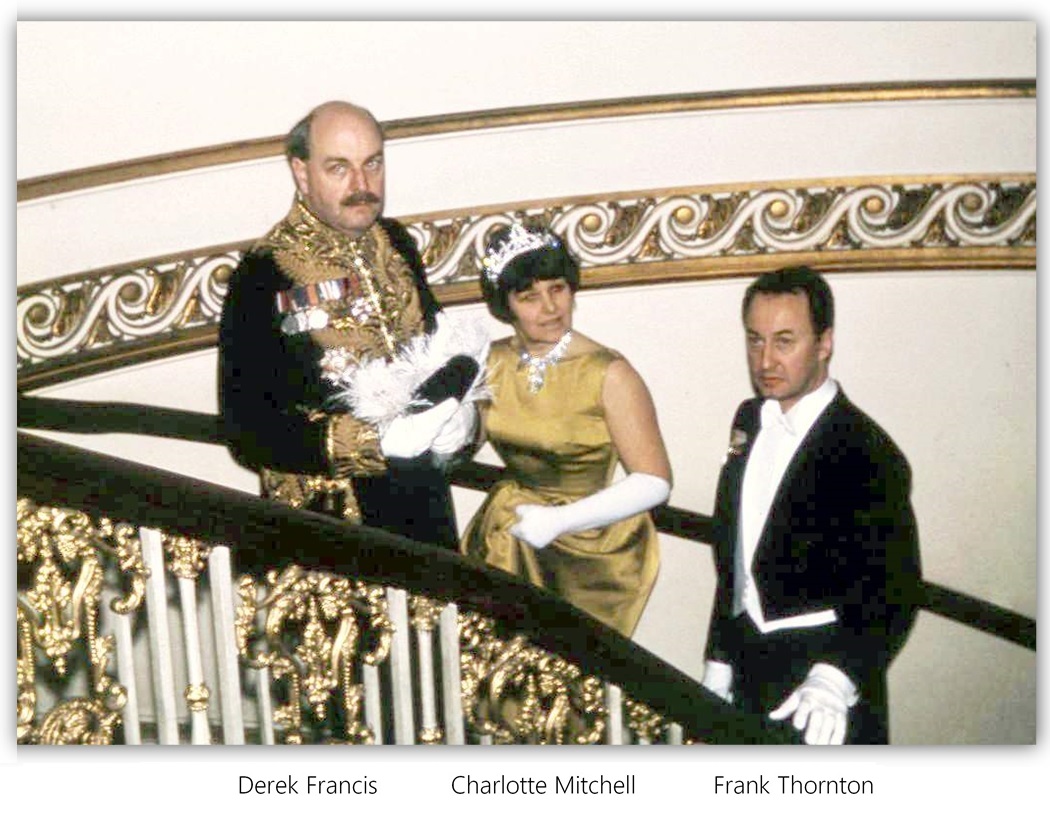

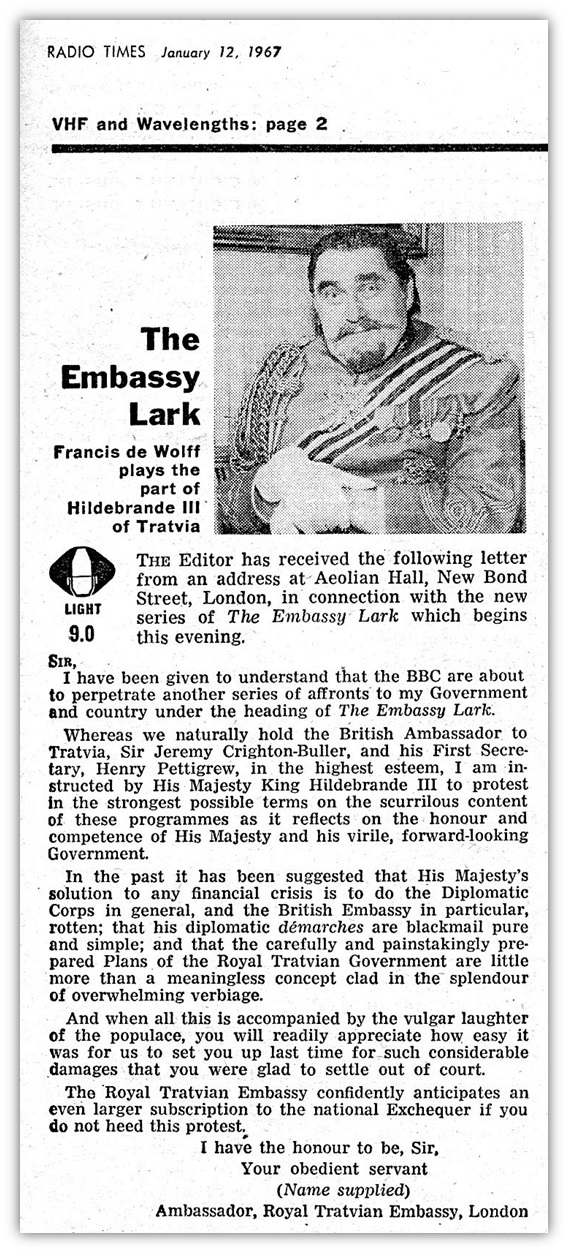

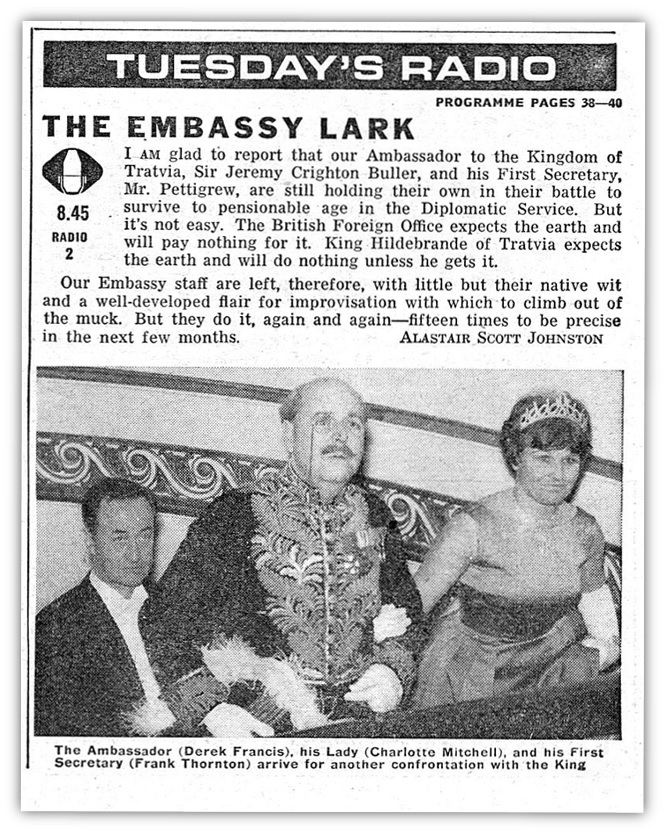

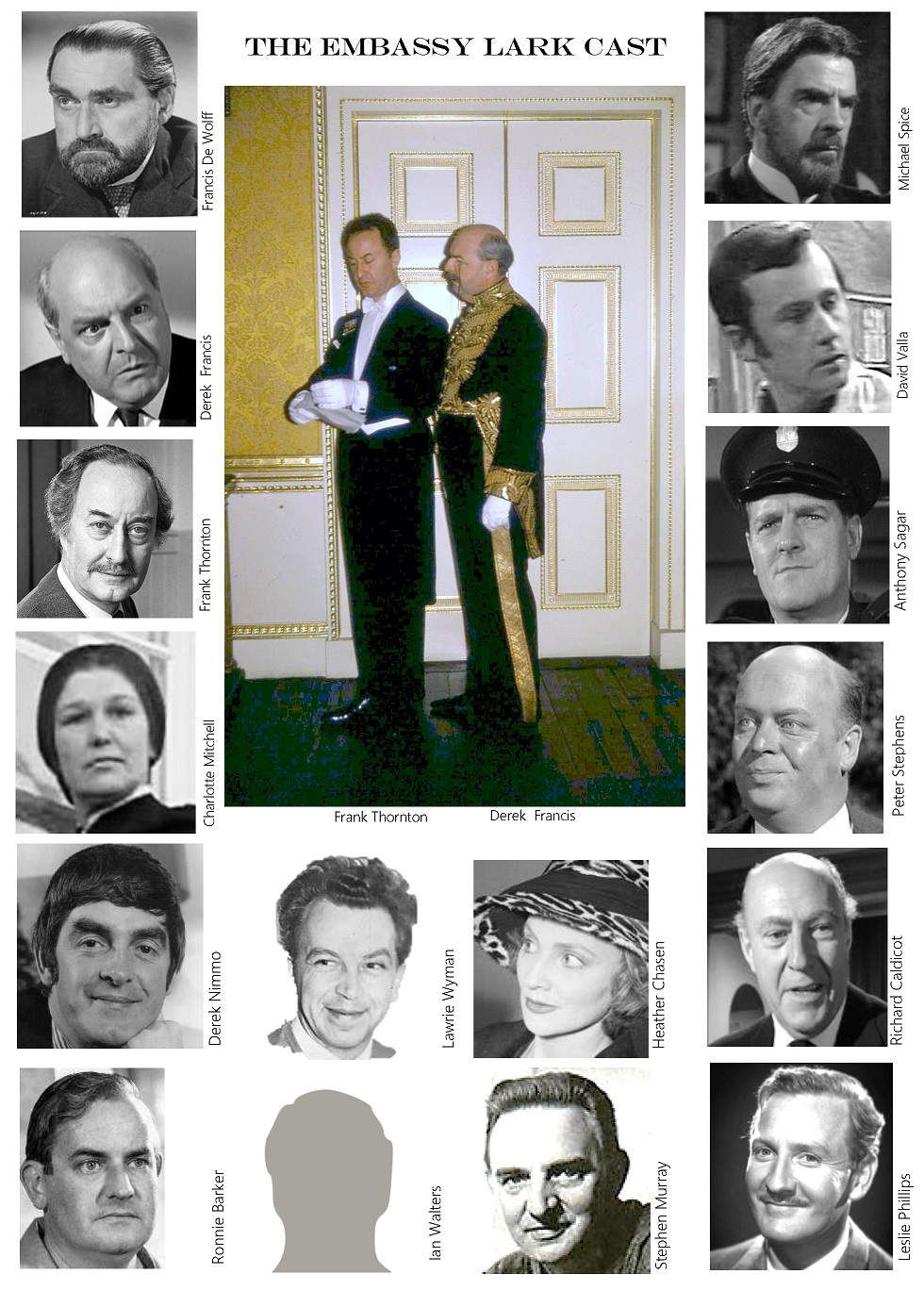

Despite Tratvia being the host country, the British Embassy is the centre of most stories. Derek Francis plays His Excellency Sir Jeremy Crighton-Buller KCMG (Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George, a British order of chivalry founded in 1818 by George, Prince Regent, later King George IV). Charlotte Mitchell is Lady Daphne Crighton-Buller and Frank Thornton is Henry Pettigrew. He also played Commander Fairweather in `HMS Paradise’ 1964/65, ITV`s version of `The Navy Lark’, all 26 episodes of which were not preserved. Francis de Wolff is the impecunious ruler of the country, constantly seeking financial benefactors (a character trait formerly associated with CPO Pertwee). Two and sometimes three more actors created new voices for the various characters Lawrie needed for a particular week’s adventure.

There are no catch phrases such as “Left hand down a bit” or “Lummy” to induce laughter but we do encounter ‘Blasted Sidney’, a chauffeur, along with Russian and Chinese voices together with British accents at the various functions. The cast of seven is occasionally augmented by a Navy Lark regular in character or as a supplementary attaché to one of the various Consulates.

Laurie Wyman's slightly smaller ensemble remained very much the same as in both ‘The Navy Lark’ and ‘The TV Lark’ with incompetent individuals in positions of authority constantly making a mess of things yet fooling their superiors that most of the time they were coping.

The manner in which the stories unfold establishes how the minor diplomatic outposts staffed with less career orientated individuals from dissimilar countries appear content to maintain social niceties with their host country by any means, which includes regular gifting to the sovereign. It remains crucial to the most inept of diplomats that whilst being hundreds of miles away from government, staff have to be seen to exhibit confidence and professionalism - not forgetting the essential qualities of tact and diplomacy that every overseas envoy needs. Mindful of international diplomacy, we encounter envoys trying to be very careful to understand how politics and power work in alternative cultures. Failure to be sufficiently sociable or benevolent, not to mention discreet, can mean that there are consequences (e.g., Sub Lt Phillips’ missing navigational skills).

This being a 1960s radio comedy programme, the content of the stories and circumstances were mainly drawn from both situations and characterisations lived and learned at that time. Norms of the day were very different, with the majority of people settling for a life of routine and very few people able to holiday abroad; so first-hand experience of different lifestyles came through books, magazines and the media. To this end, actors used the same memes - be they in cinema or television - to portray a overseas ambassador. On radio, all you have is sound to identify each actor in turn. Good casting means the listener can ‘see’ each person as they speak, not struggle with similar voices trying to differentiate each character.

Twenty first century commentators are currently all too quick to negatively suggest that ‘silly’ voices are “xenophobic’, and that alternative cultures are being belittled by inconsiderate lampooning of accents. It is evident that criticisms of `The Embassy Lark’ accents come from a need to assert ‘Political Correctness’ on a sixty year old performance from a time when attitudes were different and the family audiences of the day held the show in high esteem. Today’s comic performances frequently use expletives with impunity and are frequently totally self-obsessed as they scream and shout at their onlookers throughout their routines. How these shows will ‘age’ across time is anyone’s guess.

The legacy of the taped shows we have so far acquired from home recordings can often be most definitely hard work on the ear due to poor tape or low quality signals from medium wave radios at the time of day the show was broadcast. To date, we have been fortunate to be given three different collections from very different reel to reel sources around the UK but we are still struggling to offer 42 quality broadcasts despite careful re-mastering. Alternative prime source recordings are still very much sought and if you have any reels labelled ‘The Embassy Lark’ do contact us and we will organise digitalisation.

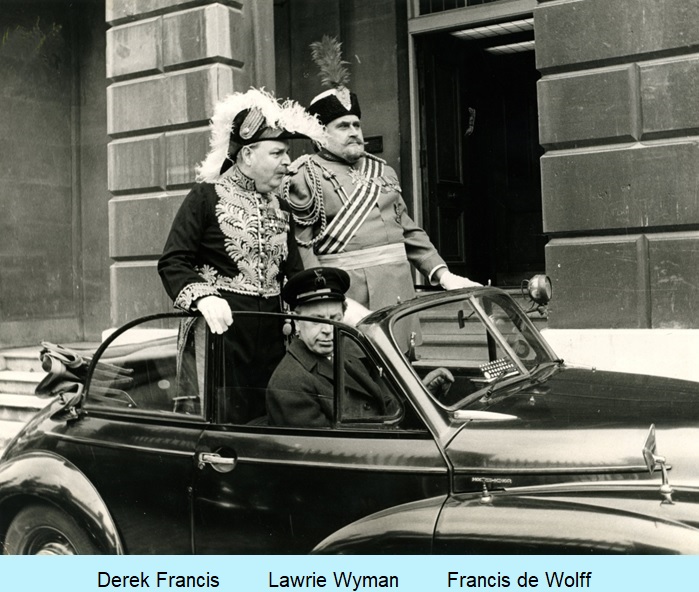

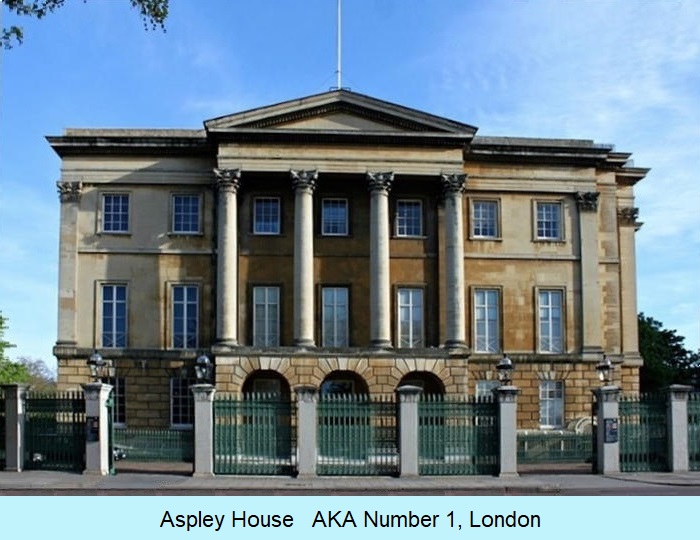

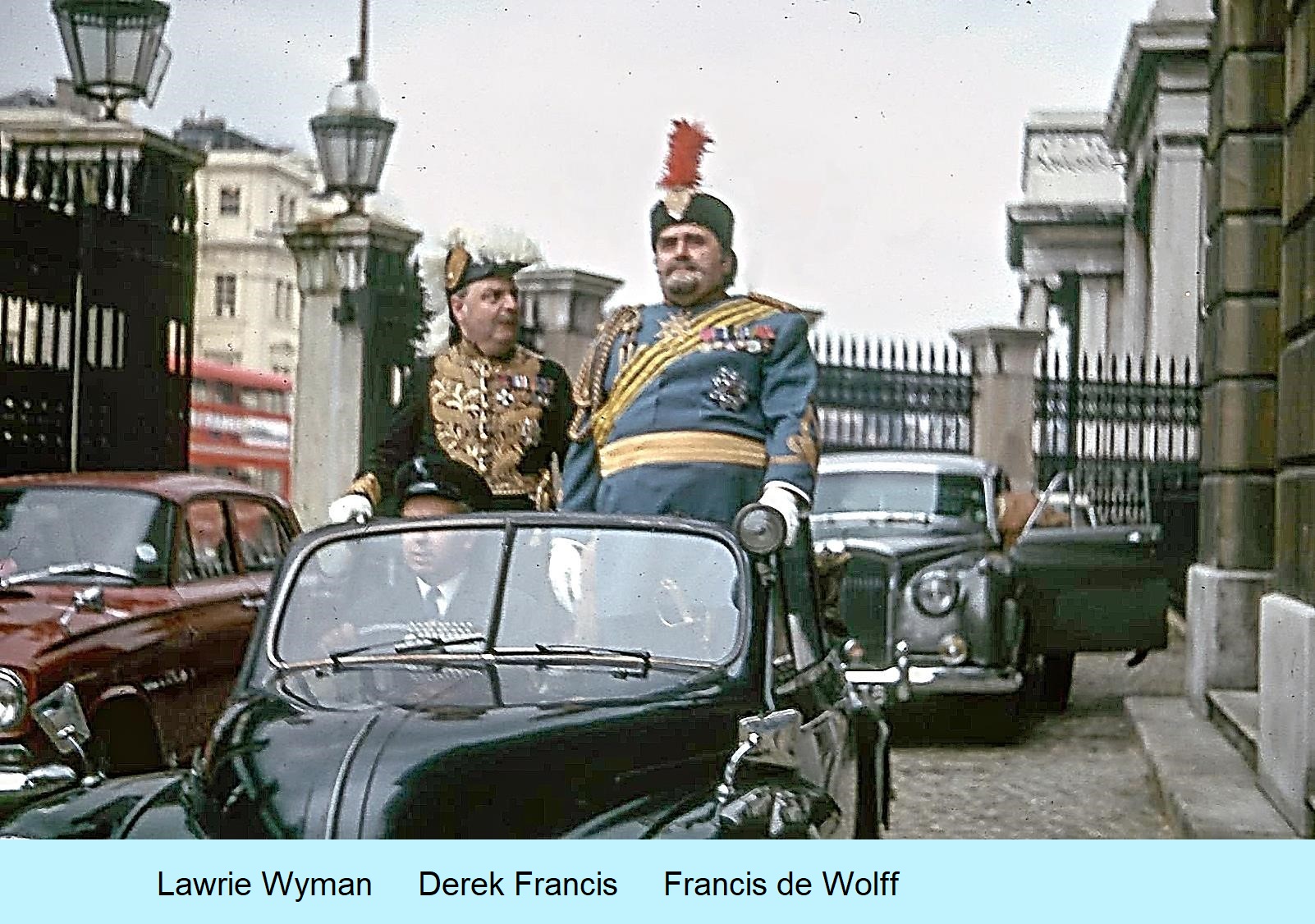

What we do have though is a delightful collection of photographs of some cast members taken by the Radio Times photographer, and colour slides by Evelyn Wells who shot the location snaps on slide film (by accident) and had to wait 50 years to see a print.

This black and white photograph of Francis de Wolff and Derek Francis standing up in an open top car is particularly interesting. The exterior shot is taken at Apsley House also known as Number 1, London. The black Morris Minor was owned by Evelyn and the driver in the car is Lawrie Wyman wearing the gabardine raincoat of the porter at Apsley together with his cap.

In a colour photograph of that scene taken by Evelyn you can see a Bentley behind the Morris Minor. Look carefully to see a man in a sheepskin coat getting something from the vehicle. That car belonged to Lawrie, who was apparently a car enthusiast. The person retrieving something from Lawrie’s posh limo is Alastair Scott Johnston.

Evelyn took further colour images inside the building at the same time as the official photographer. Various of the official shots were subsequently used in Radio Times over the next two years when features were written to promote the series.

The Embassy Lark has not been a regular visitor to the airwaves following its original broadcasts due to the complete disposal of the entire show during a tidy up of the stock cupboard at some point in the past. One of our members had emptied a very large skip (dumpster) of BBC vinyl in the 80s, but not one Embassy Lark was in there. Many well-known ‘Golden Age’ shows were found, but the complete absence of Embassy Lark recordings perhaps indicates that the programme was lost much earlier.

Text © Fred Vintner, 2021.